In the book, The Boys in the Boat, by Daniel James, the book’s Zen Master, George Pocock, gave Joe Rantz these words of advice: Once you row past the pain, the exhaustion, the voice that said it can’t be done, then strive to work in harmony with the others in the boat, trust the others in the boat, and when you do, “you will feel as if you rowed right off the planet and are rowing among the stars.” With Joe and seven other depression-era working class boys rowing in perfect sync, Joe’s team stole the 1936 Olympic Gold from Nazi Germany.

Now imagine fifty very different rowers that have to row in perfect unison. Only the race isn’t for gold. It is for lives. Millions of lives.

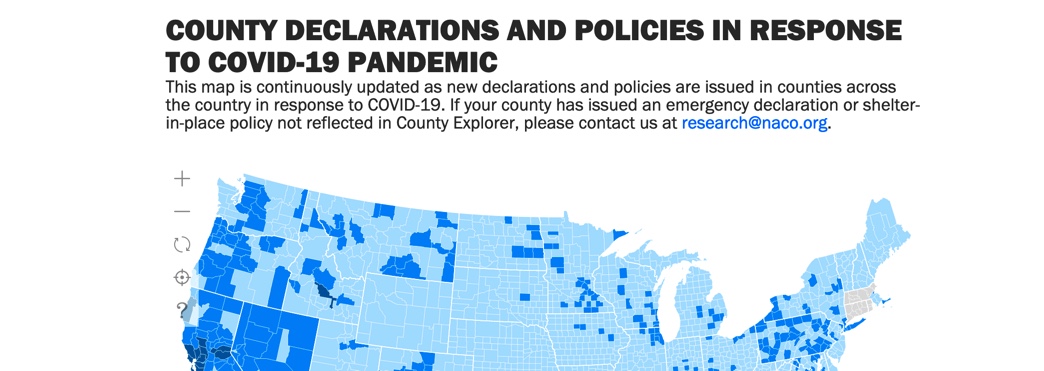

Today, states and counties in the US have a myriad of different COVID 19-related county declarations and policies. They vary dramatically, even across neighboring states. This is a big problem, with life and death consequences. Counties need stronger state leadership, and states must cooperate at unprecedented levels.

All fifty states have declared states of emergency. But even under these declarations, counties pursue their own policies. And their public health offices or local governments often have to seek approval from the state health officer or the governor’s office before implementing stricter closures than those imposed by the state.

Counties throughout our nation have often been out in front of their states in implementing COVID 19-related closures and limits on public gatherings. Teton County, Wyoming, gateway to Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks and home to three ski areas including the popular Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, recognized the threat that remaining open for businesses would pose to a small, rural health care system. Local leaders and health officials knew the resorts, restaurants, bars and shops—all incredibly reliant on tourist—had to close. Supported by the local town and county governments, the Teton District Health Officer had to craft his own resolution and request approval from the State Health Officer in order to implement it. Shortly thereafter, the Governor announced state-wide closures.

However, at the time of writing, just over the border, Idaho merely recommends that “organizers (whether groups or individuals) postpone or cancel mass gatherings and public events” with over fifty people or more. That despite the fact that as many as 10,000 residents of eastern Idaho commute daily back and forth across the state line. Teton County, Idaho later implemented closures similar to those in Teton County, Wyoming. But elsewhere in Idaho, closures and restrictions vary widely, from the minimum required by the state to shelter-in-place restrictions in Blaine County—home to Sun Valley Ski Resort and the hardest hit county in Idaho—to bans on visitors entering from regions “that have sustained widespread community transmission” in Custer County.

Similar patterns of disparate county-level restrictions exist across the nation. In much of Kansas restaurants and bars remain open. In New York, Illinois and California the hardest hit counties have implemented shelter-in-place policies. While hard-hit Washington state has not gone that far.

A lack of a coordinated response will likely result in nationwide infection rates almost uniformly above 75%, with catastrophic implications for local health care systems. If one state closes all non-essential businesses, people can simply go to the next state to do their business or recreate. Crowded public gatherings in bars, restaurants and other public venues combined with unchecked travel by virus carriers with mild or no symptoms will drive exponential growth in transmission. In this same light, non-essential domestic air-travel has not been prohibited. How can local leaders seek to protect their communities and states when airplanes continue to traverse the nation, providing perfect vectors of disease transmission?

Unless every state and county puts in place strict measures to close public gatherings and limit travel, we are not going to flatten the curve, and health care systems across our country will be overwhelmed.

The ethos of the United States is firmly rooted in individual rights and freedoms, so the only way we can really change the trajectory of our current patch-work set of controls is for all states to work together. This can be done through groups like the Western Governors Association, where currently there is a list of initiatives to tackle regional issues such as stemming the spread of invasive species, but where there’s no indication of any form of coordination around preventing the spread of COVID 19. Region-wide efforts could quickly be amended and adapted to match those of neighboring regions, especially with leadership and guidance at the federal level, thereby creating a cohesive national strategy. This is essential.

To forge a gold-medal team, Pocock told Joe to “think of a well-rowed race as a symphony, and himself as just one player in the orchestra. If one fellow in an orchestra was playing out of tune, or playing at a different tempo, the whole piece would naturally be ruined.” Our nation’s states and counties need to pull together now if we are to avoid the worst-case scenario.

We cannot delay.