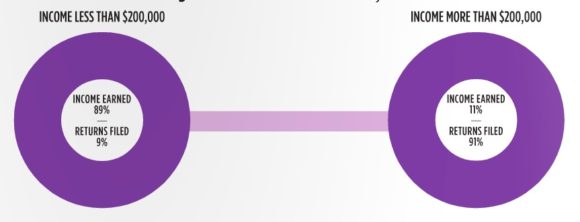

These two graphics, the first borrowed from the Jackson Teton County Housing Authority, the second from Jonathan Schecter’s Jackson Hole Compass, are what an imploding middle class looks like: median home prices completely detached from a community’s wage reality that drive an ever widening wedge between the haves and have-nots.

When the world discovered Teton County—bucolic, quiet, neighborly; surrounded by wooded hills teeming with wildlife; next door to some of the finest protected public lands in the nation—we became the it place to live. And when Teton County became the it place to live, the world opened its wallet and started buying it up, parcel by parcel, home by home, condo by condo.

Locally-earned wages haven’t kept up to the value placed on our land by the global market. Indeed you’d need a county full of the world’s top financiers/entrepreneurs/scientists/sundry 1%’rs to generate local wages that match local real estate prices—a mix one might expect in downtown Manhattan, or Silicon Valley, but not here. Our economy is tourist-based with average annual wages hovering in the mid-20k’s. Sure there’s some construction and wealth management here too. But the overall mix leaves the median income around $65,000 (around $95,000 for a family of 4), or well short of the market price set when global demand intersects with a miniscule supply of developable private land.

In economic speak, our real estate market is “distorted.” Why does this matter? Because the market is indiscriminate. It does not care if the best teacher can’t afford a home here. It does not care if your hospital staff is a nurse or two shy because they’re commute is blocked or congested. Or if the mental health provider responding when a kid is suicidal lives too far away to prevent a preventable tragedy. It does not care whether there are 50 volunteer firemen and women nearby to fight a fire, or 5. The market simply says either you can afford to live in Teton County, Wyoming, or you can’t. And right now, many can’t.

Losing entrepreneurs is one thing—our community becomes less vibrant as they take their energy, passion and creativity to enrich other communities. Losing health care workers that serve rich and poor alike is another. Or losing teachers that ensure the best quality education for our youth, or veteran peace officers who know our community and its quirks, or construction workers who also volunteer as fire fighters, or wildlife biologists and game wardens who monitor and defend our wildlife and ecosystem.

“Subsidized housing!? Doesn’t a tax dedicated toward housing just mean growth, urbanization and a handout to the private sector and ski bums!?” worry those opposed to this policy. “Let the market sort this out,” they might say.

But can we be so sure that laissez-faire policies will result in less growth? As the world’s deepest pockets continue to see gold in our green pastures, the price of even small lots that normally target middle class workers keeps going up. And up. Last I checked, town-size lots cost around half a million dollars, and there were only 5 homes on the market priced less than three quarters of a million dollars.

You can fit a lot of town-size lots on a couple hundred acres of ranch land. But would you price them to sell to the local work force?

You’d likely design them to attract the broadest possible demand, especially the very wealthy. Perhaps you’d use your water rights to make a few ponds, enhance some trout habitat. In the ultimate laissez-faire world you’d make them short-term rentals. Then you’d trickle them onto the market so that a flood of supply doesn’t drive down prices. In so doing you’d double, triple, maybe quadruple the asking price over what you would get selling to Teton County’s local work force.

Thus it’s unlikely that goosing the supply of market lots to the tune of hundreds of new units will provide the workforce housing one might expect. In the face of demand from the global one-percent, a developer pricing lots that locals can afford would be leaving money on the table. Sure we’d require 25% of the total to be deed-restricted workforce units (see LDR division 7.1.4.E). But 25%? That’s hardly going to house the workers filling the jobs created by the other 75% market-rate units, let alone replace the 8,000 or so existing units already leaking out of the aging hands of long-time residents and workers.

And even if piling on supply were to provide workforce housing, for a time, how would it impact our wildlife and open space values? What would a free-market ramping up of supply do to our over-all build-out? How could it possibly fit our town-as-heart, community-first-resort-second vision?

It can’t. Markets deliver critical information via price signals. But free-market policies need to live in a practical, real world context. In Teton County, a free market solution to our housing and community health challenges would lead to growth for growth’s sake at the expense of our core values.

Out of concern for those core values, we’ve put the brakes on growth. Recently implemented land development regulations removed around 2,400 potential units from the rural county. Even if only half of those units would have ever been built—higher end homes one and all—we’re still well-below build-out numbers hashed out during the drafting of the 2012 Comprehensive Plan. In fact we’re knocking even more than that off of our overall growth because about every four high-end homes requires another dwelling unit’s worth of workers to build it, care-take it, and provide services to its inhabitants.

The way to stop growing is not to gut the middle class and cut the lower class off at the knees. The health and welfare implications are too dire: over-crowded, cost-burdened, dilapidated housing is already Teton County’s second highest rated health issue. Twenty percent of county households have severe housing issues, meaning that a household lacks complete kitchen facilities, lacks complete plumbing, is severely overcrowded or is severely cost burdened (costs including utilities exceed 50% of monthly income). The collateral damage of severe housing costs us tax dollars too, whether it’s for expensive emergency care or broader and more comprehensive safety nets.

Voting to approve a penny of sales tax, half of which would go towards housing (the other half towards transportation alternatives to single occupancy vehicle travel), allows local government to target housing towards the middle class and protect community character without blowing the lid off build-out numbers. Investing half of that penny in housing can subsidize new construction through various channels. It can also be used to purchase easements on existing homes, keeping existing stock in the hands of workers while justly compensating owners expecting a market price for their property. The former targets housing exactly where the Comprehensive Plan calls for it: in our complete neighborhoods, not out in important wildlife habitat and open spaces. The latter adds no new housing, helping ensure we remain within the community’s vision for build-out.

A severe housing shortage locks in the extreme gap between the haves and have-nots, destroys community vitality and drains hope. Voting to approve the sixth penny protects space for middle class families to thrive without trying to build our way out of the problem only to the detriment of our wildlife and open spaces.

Thanks for an articulate, well-reasoned picture of what is at stake and what we can do.

This perfectly characterizes our personal conundrum,Mark. Both health care workers,we would love to return to Jackson, a place we still consider home after living there almost two decades. It is our community and we care deeply for the place and the people. Alas, with kids to feed,clothe,ski and potentially send to college, moving back seems far beyond our grasp.

Nicole–I hope you guys are doing well. Thanks for reading, and thanks for the comment! We’d love to have you back here for your nursing experience, Evan’s medical knowledge and abilities, and for the joy of seeing your kids. Please do stay in touch. All my best!

Mark

Suburban sprawl to create more unrestricted housing stock is a bad idea.

Public money to subsidize housing for public sector workers on land the public already owns is a great idea.

Public money to buy land on the free market for housing for private sector workers is unsustainably expensive and and inappropriate subsidy for private business.

Density bonuses in the walkable urban commercial core exclusively for deed restricted employment based housing with no rent or price caps will reinvigorate our local affordable housing market.