This is the text of my speech at the Charture Institutes 22 in 21 Conference held in January, 2017:

Good morning everyone. Thank you for being here today and for caring enough to be here today. And thank you, Jonathan, for creating this event back in 2012. More importantly, thank you for your passion and commitment to protecting and preserving our community.

Thanks to the past election, we politicians have been liberated once and for all from sticking to the facts. Thus what follows may or may not be true.

1.What has changed in the past year?

A looming change is that county and town governments soon stand to lose about $12 million in revenue. That’s because last fall I asked you to approve a second optional penny of general revenue rather than the traditional second penny of specific purpose revenue. You chose no, and I’m still eating crow.

That second penny of optional sales tax is also referred to as the sixth penny because the county currently collects six pennies of tax on every dollar of sales. The state keeps 61% of the first four pennies. That’s mandatory. Counties are allowed to add up to 3 cents beyond those four and keep 100% of the revenue. Those are optional. There are two types of revenue that can be generated by an optional penny. One is general revenue that can fund both capital projects and government operations. The other is specific purpose revenue, or SPET, that can only be used for the specific purpose ascribed to those revenues on the ballot. Two of the three optional pennies can be SPET and the third general; or two can be general and the third SPET. But they cannot all three be either general or SPET.

Teton County currently collects 1 optional penny of general tax revenue, aka the fifth penny. This penny was forced onto the ballot through petition by 5% of the electorate in 1973 whereupon it was approved by a majority of voters. From ’73 to ’89 it was re-approved by voters every 2 years. From ’89 to 2002 it was re-approved every 4 years. In 2002 it was made permanent by resolution.

Teton County also collects one penny of SPET. SPET was first put on the ballot in 1985 in order to pay the bond on a new jail. It has been re-upped by voters every two to four years since and funded about 50 capital projects that include wastewater infrastructure, schools, libraries, rec centers, transit infrastructure, energy efficiency improvements, pathways, fire trucks and workforce housing. So, since 1985 Teton County citizens and visitors have paid six pennies of sales tax on every dollar spent for the purchase of most goods. Groceries are exempt.

The last time voters approved the sixth penny of SPET was in August when you approved $6 million to stabilize the landslide threatening Broadway and the town’s water main. However because SPET was not on the ballot in November, and since the sixth penny of general that was on the ballot lost, once $6 million has been collected, which will by the end of February, 2017, the county sales tax rate will drop to five cents. It will remain at five cents until action is taken by either the joint elected bodies of the town and county or by 5% of the electorate forcing a general penny back onto the ballot.

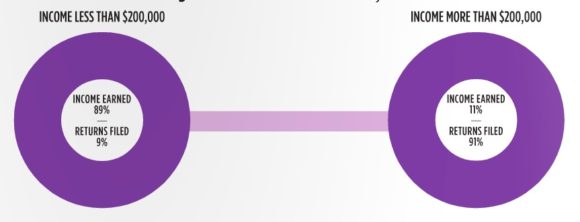

A full penny of sales tax brings in about $12 million a year. General revenue, like that brought in by the existing fifth penny, is divided between the town and county at a 45/55 ratio based on the population split in 2010. In the 12 months spanning July 2016 through June 2017, the county expects to collect, and spend, $16 million in general sales tax revenue comprised of 31% of the first four pennies and 55% of the fifth penny.

The county will also collect $7.8 million in property tax amounting to 9 out of 12 possible mils we could levy.

The county’s third largest source of general revenue will be about $2.2 million from the federal government paid to Teton County in lieu of property tax we don’t receive because the Feds own 97% of our county. Or We, capital W, own 97% of our county, depending on how you look at it…Those are our PILT revenues. By the way, if the state were to take over our federal lands, as Wyoming state senate majority leader Eli Bebout favors, a good question to ask is whether Cheyenne would take over and continue those PILT payments?

Once all revenues are accounted for, we will have $37 million dollars to spend, otherwise known as “Blank Checks.” After returning from our publicly funded beach vacation, commissioners will use the rest of our blank checks to fund all the usual operations of government. Fire trucks will still put out your fires; the Sheriff will still pull you over in low-mileage Chevy Tahoes that can outrun any other SUV on the road; public health will still very likely prevent a contagious disease from wiping us all out; emergency management and the county coroner will take care of the mess if disease somehow does spread; planning and building will still be here and be just as much a pain in the ass as ever; the library will be open; the rec center will be open; and roads, bridges and intersections will still get repaired during peak traffic in July and August. In short, government will continue functioning in all its glory.

What you won’t see are the types of capital projects that SPET has funded in the past. You know….fire stations…like whatever….

So some might say government has been right-sized. But it has not so much been down-sized.

Back to the sixth penny. What did I intend when I asked you to approve that second penny of optional general sales tax revenue? I intended to use it to protect our community character. Here’s how. If you have a pen and paper, please draw a vertical rectangle in one corner and divide it into three horizontal equal parts. Each third is the floor of a building you own in downtown Jackson. Fill in each floor with its most lucrative use. Mine looks something like, art gallery on the first floor, real estate offices on the second floor, and luxury townhomes meant for short-term rental on the third floor. Now draw a large rural parcel in the county over 140 acres in size. Make one side kind of wavy because that boundary is somewhere between the levies constraining the Snake River. Fill in your parcel with its most lucrative use. If you drew a ranch, you fail. Ranchers and climbers have at least one thing in common. If you give each of us a million bucks, we’d keep on ranching and climbing until it’s gone.

Now ask yourself, “How much community benefit did I just provide in my three story building downtown and in my large rural parcel?” “How much workforce housing?” “How much open space?” On the flip side, ask yourself “How much more workforce housing does the community now need to build to staff and maintain my new development?” If the answer is 0 to the first three questions and something well above 0 for the latter question, ask yourself, “How many cars did I ad to our network of two-lane roads?” If you drew nothing but dense workforce housing, ask yourself, “Did I leave room for wildlife?”

Now ask yourself, “How might I reconfigure my development plan to provide both workforce housing and more open space instead of more commerce, more lodging and more second homes?”

Finally ask yourself, “How best would I like the community to support me, the property owner, in achieving this reconfiguration that develops my property in a way that supports community values as well as earning a fair return on my private property?”

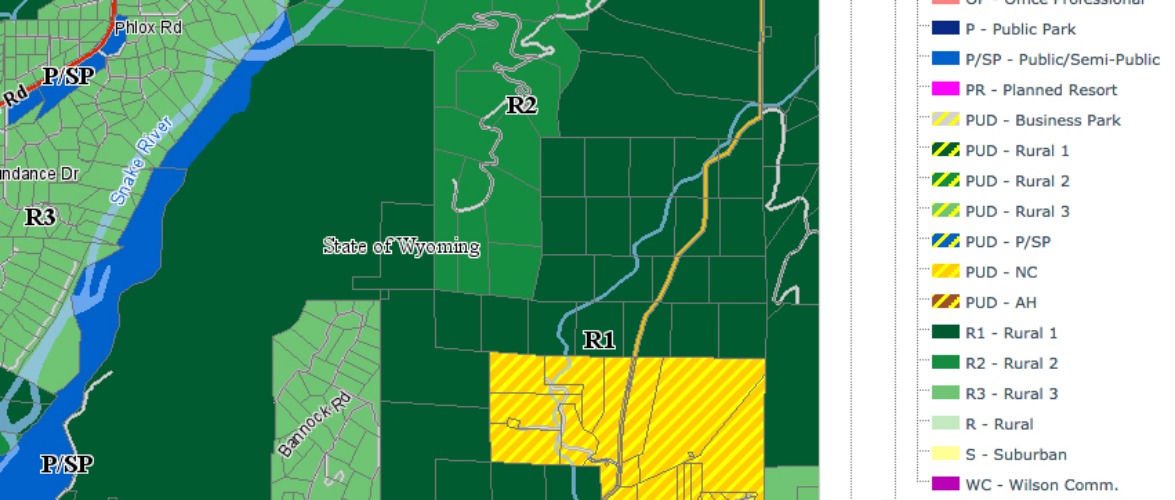

Now draw a large screw, and label it LDRs, for land development regulations. LDRs restrict private uses of property for the greater good of the community.

Go back to your drawing of a large rural parcel. For a couple or more generations you believed that what you just drew—your parcel’s most lucrative use—was your absolute right. Imagine that one day you woke up and were told that overnight the county wrote about 700 pages of byzantine LDRs that dictate in detail what you can do with your large rural parcel, and that those uses allow very little of what you drew on your parcel of private property.

Would you feel screwed?

Is there a better way to achieve workforce housing and open space?

Let’s think about what was done for ranchers when wolfs were reintroduced (wolves—government sponsored terrorists, I believe the bumper sticker reads). Compensation was achieved via a fund established through Defenders of wildlife. Here’s a quote from their website: “Our goal is to shift economic responsibility for wolf recovery away from the individual rancher and toward the millions of people who want to see wolf populations restored. When ranchers alone are forced to bear the cost of wolf recovery, it creates animosity and ill will toward the wolf. Such negative attitudes can result in illegal killing.”

Why couldn’t this read, “Our goal is to shift economic responsibility for open space and work force housing away from the individual rancher and toward the millions of people who want to see expanses of rural open space, ranching, wildlife and a rich and diverse community in Teton County. When ranchers alone are forced to bear the cost of maintaining open space and providing low-cost housing, it creates animosity and ill will toward county commissioners. Such negative attitudes can result in ranchers hanging me up by my thumbs and probably not voting for me.”

My intent for the general penny, was to compensate private property owners for not building second homes or short-term rentals and instead building workforce housing in complete neighborhoods. My intention was to compensate private property owners for preserving open space, weed-free and wildlife friendly.

Now it’s up to the private sector. To be sure buying conservation easements is nothing new. The Jackson Hole Land Trust, The Nature Conservancy, and in the case of the Antelopes Flats parcel, the Grand Teton National Park Foundation, have funded the preservation of huge amounts of critical and iconic open spaces throughout Teton County and northwestern Wyoming. In fact they’ve been so successful that open space was left off the list of community priorities that revenue from the sixth penny was meant to address (the other two being housing and transportation). That said, as Teton County doubles again in population, there are sure to be critical bits and pieces of migration corridors and habitat that these organizations might miss. I believe we would do well to consider maintaining a source of public funds that could be deployed, probably in partnership with private funds, to preserve these spaces.

2. What can people expect in the coming year?

A SPET ballot, most likely in May and most likely looking like any other in the past with very little funding of workforce housing outside of town and county employee housing.

3. What keeps you awake at night? What gives you hope?

All of the above keeps me awake, and all of you give me hope.

4. What is the one thing individuals can do to address our biggest challenges or realize our biggest opportunity?

I think the concept of compensation rather than LDRs is one of the ways we can address our biggest challenges. The private sector needs to lead the way. This is important and merits discussion beyond this speech. How it’s going to pan out for the private sector to compensate private property owners for the provision of local workforce housing I don’t know. The private-sector may also be challenged to produce transportation solutions to avoid a non-functioning road network or WYDOT-imposed widening sooner rather than later.

5. What is the big point to take away today?

Please take your drawings home and hang them on your refrigerator.

Thank you everyone! And if there’s time, I’ll entertain a question or two.