This is the talk I gave at the latest 22 in 21 on January 18th, 2018:

What is the state of our jurisdiction? I’d characterize it as one of struggle, an epic struggle, with ourselves, to define the value of our natural environment. Without measures of value for the ecosystem and associated ecosystem services, I fear we cannot meaningfully address how to “preserve and protect the area’s ecosystem in order to ensure a healthy environment, community and economy for current and future generations,” our stated commitment in Teton County’s Comprehensive Plan. Should we, can we, put a dollar value on the area’s ecosystem, the area’s ecological amenities, the area’s open space, it’s wildlife, it’s life, it’s wildness?

To highlight this struggle, let me ask you this. Defining “the area” as Teton County, Wyoming, what is the dollar value for an intact, healthy, resilient ecosystem? If you’re like me, you don’t even know where to start.

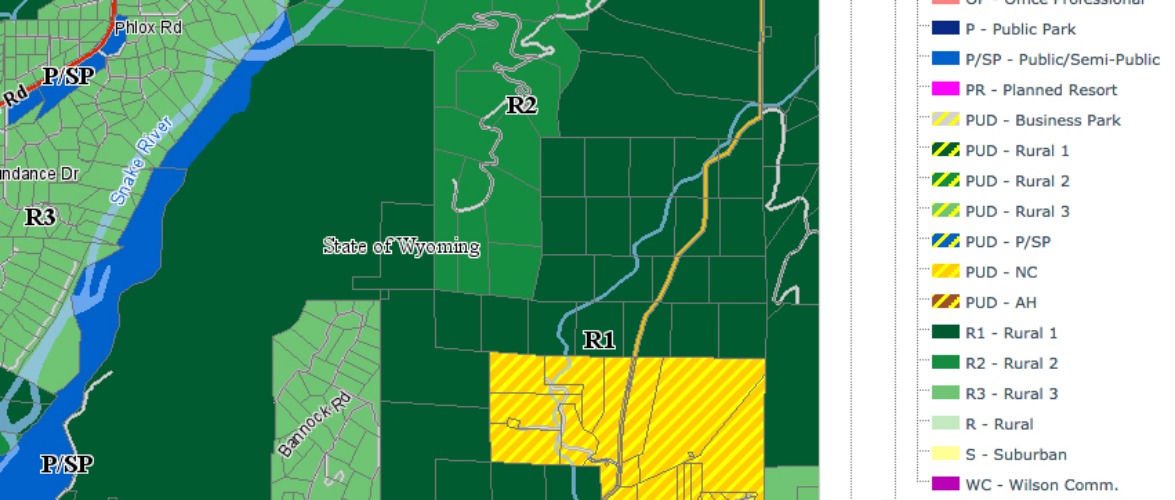

Let’s dig in. Teton County has a bit over 4,000 square miles, or 2.7 million acres within its borders. Of that roughly 76,000 acres are privately owned. Of that, roughly 21,000 acres are under some sort of conservation easement to protect some combination of scenic, agricultural or wildlife values. The remaining 200 million or so acres are public lands, much of which are to be conserved mostly unimpaired for future generations. 45% of the county lies within Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks; 51% lies within the Bridger-Teton and Caribou-Targhee National Forests, including significant tracts of Big W Wilderness in the Teton, Jedediah Smith and Gros Ventre Wilderness areas. And about 1% lies within the National Elk Refuge.

All that public land harbors substantial wildlife populations. You likely know better than I. 10 or 15 thousand elk, a bunch of buffalo, five or six hundred grizzly, wolves, coyotes, a few scraggly moose (I guess I wouldn’t look so good either if I had to stand around outside all winter eating nothing but celery). While open space on private land, due to its valley-bottom location, tends to punch above its weight in per acre importance in supporting certain species, it’s the undeveloped public lands that by and large deliver the bulk of the ecosystem services we value. Undeveloped public land keeps our air clean—imagine if all of the county were private, how much air pollution would be trapped in our valley during winter inversions. Undeveloped public land by and large keeps our water clean—runoff from mountains on public land creates an underground river to constantly flush our groundwater ensuring it’s purity. Undeveloped public land by and large harbors the wildlife in populations our private land couldn’t otherwise sustain. And undeveloped public land by and large provides the bulk of our opportunities for recreation in all it’s modern forms.

So, taken as a whole, what is this area’s ecosystem and the ecosystem services it provides worth to you? It’s an estimate, at best. Hardly even educated. Am I wrong?

Contrast that estimate, if you even tried, with the value of private property and associated private property rights held on the remaining 3% of private lands. As of July 10, 2017, the State Assessor certified that the remaining private land in Teton County, Wyoming is valued at $15,222,990,853. That’s pretty precise.

Our inability to value ecosystem services, let alone place a value on our ecosystem as a whole, is clashing over and over again with a system of private property rights rooted in principles of individual and economic freedom tracing back to the Magna Carta. (Actually I throw that out just to sound erudite. I gather politicians cite the Magna Carta when trying to look informed about such things as personal freedoms. In fact, thanks to Wikipedia, I found out it was originally about the medieval relationship between the monarch and the barons and less about individual freedoms. Although if it IS about medieval power structures, then maybe it is becoming more relevant today than we might like to think.)

The clashes are big, over things like a proposal for building a couple hundred homes on ranch land south of town, and small, over things like an osprey nesting pole blocking a view corridor of Glory Bowl. They’ve included struggles to discern whether 40 acres entitled with six dwelling units and overlain by the Natural Resource Overlay should have to cluster those six units, or cluster three, or none. They’ve included clashes over whether events like wedding parties should be allowed on large rural properties, over where and how construction should be staged amidst development in a rapidly growing resort, over additions to houses located near streams and rivers, and over what amenities ski hills should be allowed to build and if their boundaries should be allowed to change. They’ve been over whether a man-made wave near a trashed stretch of Snake River levy is an appropriate recreational amenity, whether iconic historic structures should be re-purposed to house raptors, whether 21 rural acres should have seven homes or 68, and whether fences to protect hay fields should be allowed to impede elk movement. And I can assure you that each of these clashes has good people, often friends of mine, on both sides.

There are 75 or 80 pages of land development regulations that attempt to strike a balance between the exercise of property rights and the resulting impacts to the community. They lie in Article 5, titled Physical Development Standards Applicable in All Zones. They are onerous. The late Justice Scalia once wrote regarding the reduction, in Supreme Court jurisprudence, of the protections afforded to property rights, that “economic (my emphasis) rights are liberties: entitlements of individuals against the majority. When they are eliminated, no matter how desirable that elimination may be, liberty has been reduced.” I guarantee that these 80 pages of regs governing what you can and can’t do with your property were not requested by the property owners trying to exercise their property rights. They were requested by neighbors, neighbors expressing a diminishment of their rights to natural amenities such as viable and healthy wildlife populations, natural soundscapes, and scenic vistas. But rarely is there a dollar value attached to said diminishment of ecosystem services, to that one-more-cut in the death-by-a-thousand-cuts of our ecosystem.

The government response, to craft regulations in an effort to meaningfully protect our ecosystem, has been clumsy. As Ronald Reagan said, “The most feared nine words in the English language are ‘I’m with the Government, and I’m here to help.’” The regs crafted by me and the other commissioners are job security writ large. They leave the system open for constant testing, constant probing for loopholes, so that we commissioners, typically lay people, are forced to rule on even the most minute and arcane aspects of land use law. Expensive and time consuming appeals then leave it to the District Court judge and Wyoming State Supreme Court to clean up after us.

The system is arbitrary in that it is not rooted in any real analysis, let alone valuation, of the ecosystem services in question. It is arbitrary in that it can result in reasonable development being thwarted because the process is too onerous, or conversely for unreasonable development to be entitled because the cost to challenge it is too high, the pockets of the special interest behind it too deep. It is messy.

And in general, when it comes to these battles over whether any one of those development proposals cited above might incrementally diminish “the area’s ecosystem,” who do you think will win? The private property owner who can say with a relatively high level of precision exactly how much their property will be devalued by regulation or a blocked application? Or the community and their hand-waving claim that the proposed development impairs the environment and impacts the community? How can the community rightly claim that the impairment of the ecosystem and cost to the community outweighs the reduction in value of the private property when the community can’t even put a value on what they’re trying to protect?

So…could someone, quite possibly someone who lives here, who wanted to follow in John D. Rockefeller’s footsteps and extend Grand Teton National Park right down to the Lincoln County border, could that someone cut as many checks as there are property owners, amounting to $15 billion plus dollars, lock up the land and transfer it to the National Park Service, (likely over the dead bodies of the Lincoln County Commissioners)?

Ironically, the more that buyer bought up, the more valuable anything left over becomes…right? Because whatever is left behind is surrounded by that much more space, that much more wildlife, that much more wild, offering that much more opportunity to…you guessed it “Stay Wild.” In other words, everyone wants to live here, especially if no one else lives here.

You get my gist. Clearly there IS value to open space, to wildlife and to staying wild.

Alas, we keep developing, growing, incrementally reducing open space, diminishing wildlife habitat, suffocating the environment and extinguishing the Wild. Why? How? For what purpose?

Private gain, of course. Notably the economic rights referenced by Justice Scalia are measurable. Notably they are assignable and legally defensible, rooted in principles enshrined in the US Constitution. That ain’t changing anytime soon. And as public officials we are bound by oath to uphold the law. So long as we continue to develop within the myth that we are preserving and protecting the ecosystem, the remaining private property and the rights associated with the ownership of that property become ever more valuable.

Does that mean that saving our environment from ourselves boils down to…money?

We commissioners can regulate, arbitrate, split the baby only so much. I look now, towards you, private citizen. $15 billion. That’s what the State Assessor says. But what’s our community, our ecosystem, worth to you?